A post from a couple weeks ago explained that there are instructional design models that offer formulas for assembling training in a way that captures learners’ attention, conveys content, and provides learners with an opportunity to practice and receive feedback on new skills. That post described Robert Gagne’s nine events of instruction, which is one of the more popular instructional design models and is based on cognitive and behavioral psychology.

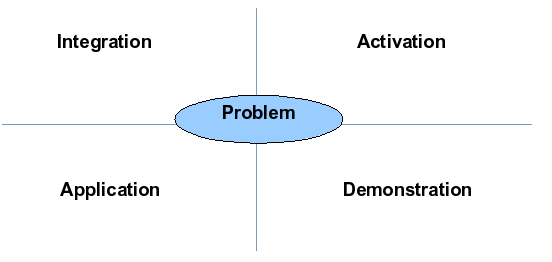

Another well-known and broadly accepted instructional design model is M. David Merrill’s first principles of instruction. Merrill built this model based on a comprehensive review of instructional theories and models in the field. The principles are a synthesis of his findings.

Both models provide sound structure for developing effective eLearning. This post mimics the earlier one about Gagne’s nine events of instruction by first defining the parts of Merrill’s model, and then applying it to a short eLearning lesson.

Merrill’s first principles consists of five principles, each with supporting corollaries.

Image from http://edutechwiki.unige.ch/mediawiki/images/9/9a/Merril-first-principles-of-instruction.png

Image from http://edutechwiki.unige.ch/mediawiki/images/9/9a/Merril-first-principles-of-instruction.png

Principle #1: Problem-Centered Learning – Engage learners in solving real-world problems.

- Corollary #1: Show Task – Demonstrate the task learners are expected to perform after they complete training.

- Corollary #2: Task Level – Engage learners in a problem, as opposed to isolated steps or actions only.

- Corollary #3: Problem Progression – Present varied problems/scenarios, working from simple to complex.

Principle #2: Activation – Relate learning to previous knowledge and experience.

- Corollary #1: Previous Experience – Direct learners to recall previous knowledge, so they can use that as a foundation for learning new knowledge.

- Corollary #2: New Experience – Provide learners with new, relevant experience to use as a foundation for learning new knowledge.

- Corollary #3: Structure – Organize new knowledge in a logical structure to help learners recall that knowledge later.

Principle #3: Demonstration – Demonstrate what learners must learn rather than simply telling them.

- Corollary #1: Demonstration Consistency – Demonstrate tasks that are consistent with the learning goal.

- Corollary #2: Learning Guidance – Reinforce the demonstration by providing learners with additional guidance, such as reference material and varied demonstrations.

- Corollary #3: Relevant Media – Use multiple forms of media appropriately in training.

Principle #4: Application – Provide learners with practice activities during training.

- Corollary #1: Practice Consistency – Design practice activities and assessments to be consistent with the learning objectives.

- Corollary #2: Diminishing Coaching – Provide learners with feedback and gradually withdraw that feedback as they learn.

- Corollary #3: Varied Problems – Provide learners with a variety of practice scenarios.

Principle #5: Integration – Prompt learners to apply newly learned knowledge to their jobs.

- Corollary #1: Watch Me – Prompt learners to demonstrate their new knowledge.

- Corollary #2: Reflection – Prompt learners to reflect upon and discuss their new knowledge.

- Corollary #3: Creation – Direct learners to create and explore ways to use their new knowledge.

If you compare this model to Gagne’s nine events of instruction, you’ll notice that Merrill’s first principles include all of Gagne’s events, they’re just described a bit differently in some places.

Let’s look at an example of how Merrill’s first principles can be applied to a short eLearning lesson. We’ll look at the same sample lesson used in the earlier Gagne post. This lesson is part of a larger eLearning course designed to teach experienced support staff in a small lending firm how to conduct quality control checks on mortgage applications. The purpose of this particular lesson is to teach learners how to identify errors.

-1- Problem-Centered Learning

Prompt learners to guess the percent of mortgage applications that have errors (could set up as a multiple choice or free response question). After learners attempt to guess, reveal the alarming statistic. Then briefly explain to learners that they can dramatically decrease that number, and outline some of the positive impacts of catching errors. Throughout the lesson, present a variety of demonstrations and practice activities.

-2- Activation

Prompt learners to identify the types of application errors they’ve heard about (could set up as a multiple response question). Ask learners to recall the consequences of those errors (could set up as a free response or matching question). Throughout the lesson, present a variety of demonstrations and practice activities. Organize new knowledge according to the application they’re learning to audit.

-3- Demonstration

Guide learners through the application, and explain how each section should be completed. Provide multiple examples of correct entries and common mistakes. When appropriate, ask questions to prompt learners to anticipate these examples based on their experience. Include audio and visual media in the demonstration.

-4- Application

Present practice exercises in which learners identify errors (or the lack thereof) on sample applications. Start by providing immediate feedback to learners about the correctness of their responses, and scale back to offering hints as needed.

Practice exercises can be peppered throughout the presentation of content and learning guidance to break up the sections of the application. A final practice exercise could be handled as a game where the learner receives points for correct responses and is challenged to earn a certain number of points.

Include a formal assessment at the end where the learner audits a few applications with varying types of errors. Provide learners with feedback after submitting the assessment and offer remediation as needed.

-5- Integration

Point learners to a job aid they can use on the job, and tell them where they can go with questions. Ensure that learners begin auditing applications shortly after they complete the training. If possible, assign learners to coaches who can check their early work and discuss their performance with them.

So why present both models?

Both models point instructional designers in the same direction, and both are broadly used and accepted in the field. It’s helpful to be familiar with a few of the models available to guide you in eLearning design, so that you can choose to follow the one that resonates most with you…or even combine elements of various models to give yourself a more complete picture.

Which model do you think about when designing an eLearning lesson? Gagne’s? Merrill’s? Another one?

Thanks for the refresher. I used Merrill's First Principles when designing a course last year for grad school.

ReplyDeleteI believe anchoring tasks in an overall problem-based approach helps to motivate learners and really incoporate many of Gagene's principles automatically-- as you pointed out in your post.

Great post

Thanks for sharing this great overview, Shelley. I have been using and researching these principles for the last several years and have found them to be quite powerful in their flexibility and usefulness.

ReplyDeleteI recently published an article that describes practical steps for applying these principles and thought I would share it here. It describes strategies based on a review of literature: http://joelleegardner.blogspot.com/2011/10/article-applying-merrills-first.html

Thanks again, Shelley! I will have to view more of your blog...

I agree with you about the power and flexibility of these principles. And the principles themselves are so simple! I checked out your link - it's a very nice summary of the literature on this. Thank for sharing it!

ReplyDeleteNo problem, Shelley. I look forward to reading more of our blog!

Delete